Your heart is like a busy train station. Blood is the train, and it has to move in one direction—forward—without going backward. If it flows the wrong way, the system breaks down. So, what stops the blood from reversing course?

The answer is simple: heart valves.

These tiny but powerful flaps inside your heart act like one-way doors. They open to let blood pass through and close tightly to prevent it from flowing back. Without them, your heart couldn’t pump blood efficiently to your lungs and the rest of your body.

In this article, we’ll explain exactly how heart valves work, what each one does, what happens when they don’t work right, and how you can keep them healthy. We’ll use simple language, no confusing terms, and real-life comparisons so you can understand everything—even if you’ve never studied biology.

Let’s dive in.

What Are Heart Valves and Why Are They Important?

Heart valves are small, flexible tissues shaped like flaps or doors. They sit between the chambers of your heart and at the exits where blood leaves the heart. Their job is to make sure blood flows in the right direction—forward.

Think of them like turnstiles at a subway station. People (blood) can walk through in one direction, but the turnstile snaps shut if someone tries to go back. That’s exactly how heart valves work.

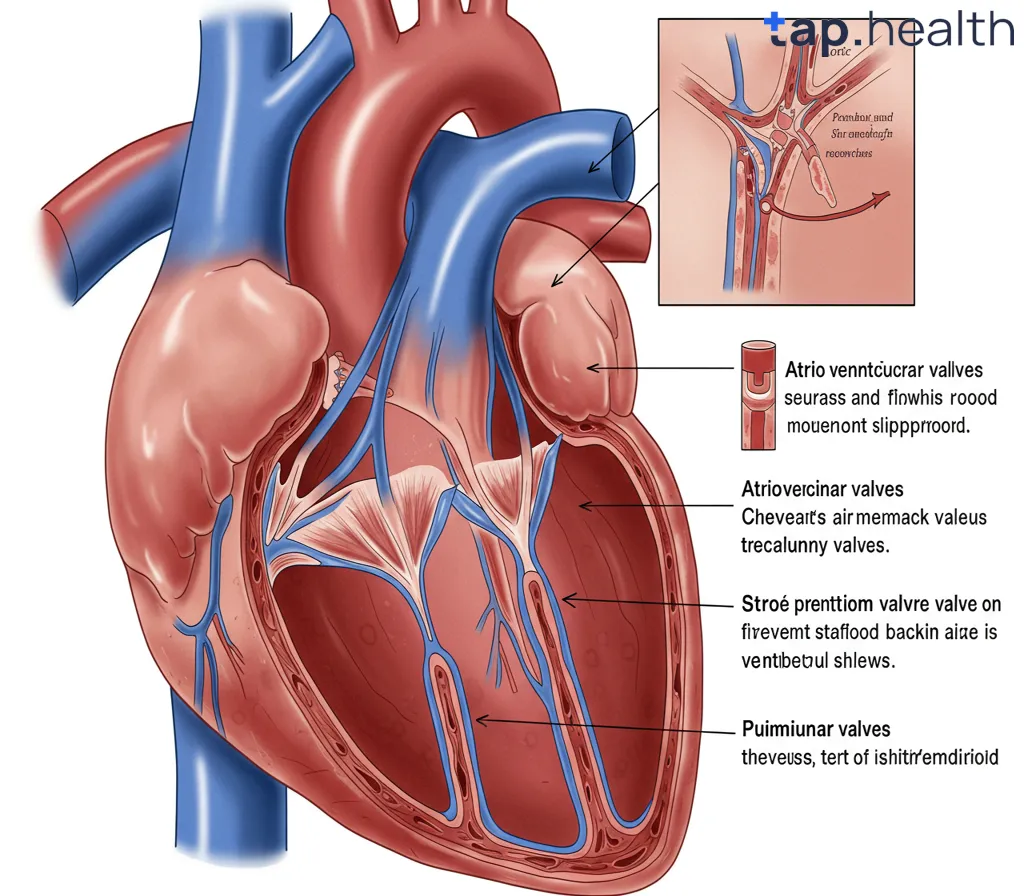

There are four main heart valves, and each one has a specific job. But before we talk about them, let’s understand how blood moves through the heart.

How Blood Flows Through the Heart

Your heart has four chambers:

- Right atrium – receives oxygen-poor blood from the body.

- Right ventricle – pumps blood to the lungs.

- Left atrium – receives oxygen-rich blood from the lungs.

- Left ventricle – pumps blood out to the body.

Here’s the journey:

- Blood enters the right atrium → flows through the tricuspid valve → into the right ventricle → pumped through the pulmonary valve → to the lungs.

- After picking up oxygen, blood returns to the left atrium → passes through the mitral valve → into the left ventricle → pumped through the aortic valve → out to the body.

At each step, a valve opens to let blood through and closes to stop it from flowing back.

Without these valves, blood would slosh back and forth like waves in a bathtub. The heart wouldn’t be able to build up enough pressure to push blood where it needs to go.

So yes—heart valves are essential. They keep the flow smooth, efficient, and unidirectional.

The Four Heart Valves: What Each One Does

Now, let’s meet the four heart valves and see how each one prevents backflow.

1. Tricuspid Valve

Location: Between the right atrium and right ventricle.

Function: Lets blood flow from the right atrium into the right ventricle. When the ventricle contracts, the valve snaps shut so blood can’t flow back into the atrium.

Fun Fact: It’s called “tricuspid” because it has three leaflets (flaps).

If this valve leaks (a condition called tricuspid regurgitation), blood flows backward into the right atrium. This makes the heart work harder and can cause swelling in the legs and abdomen.

2. Pulmonary Valve

Location: Between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery (the blood vessel leading to the lungs).

Function: Opens to let blood flow from the heart to the lungs. Closes tightly after the blood passes so it can’t flow back into the heart.

Fun Fact: This valve has three thin leaflets and is sometimes called the pulmonic valve.

If it doesn’t close properly, blood leaks back into the right ventricle. This is called pulmonary regurgitation. Over time, it can weaken the heart muscle.

3. Mitral Valve

Location: Between the left atrium and left ventricle.

Function: Allows oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to flow into the powerful left ventricle. Then it closes to prevent backflow when the ventricle pumps.

Fun Fact: It’s the only valve with two leaflets, so it’s also called the bicuspid valve.

The mitral valve handles a lot of pressure because the left ventricle is the strongest chamber. If it leaks (mitral regurgitation), the heart has to work much harder to pump blood.

4. Aortic Valve

Location: Between the left ventricle and the aorta (the main artery that carries blood to the body).

Function: Opens to let blood shoot out into the aorta. Closes tightly after each heartbeat to stop blood from flowing back into the heart.

Fun Fact: Every time your heart beats, the aortic valve opens and closes—about 100,000 times a day.

If it narrows (aortic stenosis) or leaks (aortic regurgitation), the heart struggles to supply blood to the body. This can lead to chest pain, fatigue, and even heart failure.

How Do Heart Valves Actually Work?

Now that we know the names and locations, how do these valves physically stop blood from going backward?

Let’s break it down.

The Mechanics of a Heart Valve

Each valve has flaps (called leaflets or cusps) that open and close with every heartbeat.

Here’s how it works:

- When the heart chamber is filling, the valve opens like a drawbridge, letting blood flow through.

- When the chamber contracts, pressure builds behind the blood.

- The sudden pressure slams the valve shut, sealing it tight.

- The shape and flexibility of the leaflets ensure no gaps—like a well-fitted door.

The closing of the valves is what makes the “lub-dub” sound your doctor hears with a stethoscope.

- “Lub” = tricuspid and mitral valves closing.

- “Dub” = pulmonary and aortic valves closing.

So that heartbeat sound? That’s your valves doing their job.

What Keeps the Valves from Leaking?

Several things help valves seal perfectly:

- Chordae tendineae – Tiny, strong strings (like ropes) that connect the valve flaps to muscles in the heart wall. They prevent the valves from flipping backward.

- Papillary muscles – Small muscles that pull on the chordae tendineae to keep tension on the valves.

- Proper shape and flexibility – Healthy valves are thin, strong, and move easily.

If any of these parts are damaged, the valve might not close all the way—and blood can leak back.

What Happens If a Heart Valve Doesn’t Close Properly?

When a heart valve fails to close tightly, blood flows backward. This is called valve regurgitation (or insufficiency).

For example:

- Mitral regurgitation = blood leaks back into the left atrium.

- Aortic regurgitation = blood leaks back into the left ventricle.

This forces the heart to pump the same blood over and over, making it work harder. Over time, the heart muscle weakens, leading to heart failure.

Another problem is valve stenosis, where the valve becomes narrow and stiff. It can’t open fully, so less blood gets through. The heart has to pump harder to push blood past the tight valve.

Both regurgitation and stenosis can affect any of the four valves.

What Causes Heart Valve Problems?

Valve problems can be present at birth (congenital) or develop over time.

1. Congenital Heart Valve Disease

Some people are born with abnormal valves. For example:

- A bicuspid aortic valve (only two leaflets instead of three) is the most common congenital valve defect.

- These valves may work fine for years but often wear out earlier than normal valves.

2. Age-Related Wear and Tear

As we age, valves can stiffen or calcify (build up calcium). This is especially common in the aortic valve.

Think of it like a door hinge getting rusty. It doesn’t open or close smoothly anymore.

3. Rheumatic Fever

This illness, caused by untreated strep throat, can scar heart valves—especially the mitral valve. It’s less common now in developed countries but still a major cause worldwide.

4. Endocarditis

This is an infection of the heart’s inner lining, often affecting the valves. Bacteria can stick to the valves and destroy the tissue, causing leaks or holes.

People with artificial valves or damaged valves are at higher risk.

5. Heart Attack

A heart attack can damage the muscles or chords that support the mitral valve, leading to sudden regurgitation.

6. High Blood Pressure and Atherosclerosis

Long-term high blood pressure and hardening of the arteries put extra strain on the heart and valves, especially the aortic valve.

Symptoms of Heart Valve Problems

Many people have mild valve issues with no symptoms. But when problems get worse, signs start to show.

Common symptoms include:

- Shortness of breath, especially when lying down or during activity

- Fatigue – feeling tired more easily

- Swelling in the ankles, feet, or abdomen

- Chest pain or tightness

- Irregular heartbeat (palpitations)

- Dizziness or fainting

- Heart murmur – an unusual sound heard through a stethoscope

If you notice any of these, see a doctor. Early diagnosis can prevent serious complications.

How Are Heart Valve Problems Diagnosed?

Doctors use several tools to check how well your valves are working.

1. Stethoscope

The first clue is often a heart murmur—a whooshing sound between beats. It doesn’t always mean there’s a problem, but it tells the doctor to look closer.

2. Echocardiogram (Echo)

This is the main test for heart valves. It uses sound waves (ultrasound) to create moving pictures of your heart. Doctors can see:

- How the valves open and close

- If blood is leaking backward

- How severe the problem is

It’s painless and usually takes 30–60 minutes.

3. Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG)

This test checks your heart’s electrical activity. It can show if your heart is enlarged or if you have an irregular rhythm caused by valve problems.

4. Chest X-ray

Shows the size and shape of your heart and lungs. A large heart or fluid in the lungs can signal valve disease.

5. Cardiac MRI or CT Scan

Used in complex cases to get detailed images of the heart and valves.

6. Cardiac Catheterization

A thin tube is inserted into a blood vessel and guided to the heart. It can measure pressure and take pictures of blood flow. Used when surgery is being considered.

How Are Faulty Heart Valves Treated?

Treatment depends on how bad the problem is and whether you have symptoms.

1. Watchful Waiting

If the valve issue is mild and you have no symptoms, your doctor may just monitor it with regular echocardiograms.

2. Medications

Medicines can’t fix a bad valve, but they can help manage symptoms and prevent complications. These include:

- Diuretics (“water pills”) – reduce fluid buildup and swelling.

- Beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers – slow the heart and reduce strain.

- Blood thinners – if you have an irregular heartbeat (like atrial fibrillation) or an artificial valve.

- Antibiotics – sometimes used before dental work if you’re at risk for endocarditis (though this is now rare).

3. Valve Repair

In some cases, surgeons can fix the existing valve. This is common with the mitral valve.

Repair may involve:

- Removing damaged tissue

- Reshaping the valve

- Adding support rings

Repair is often better than replacement because it preserves your own tissue.

4. Valve Replacement

If the valve is too damaged, it may need to be replaced.

There are two types of replacement valves:

Mechanical Valves

- Made of strong materials like titanium or carbon.

- Last a long time.

- But you must take blood thinners (like warfarin) for life to prevent clots.

Biological (Tissue) Valves

- Made from animal tissue (pig or cow) or donated human valves.

- Don’t usually require long-term blood thinners.

- But they wear out after 10–15 years and may need replacing.

Choice depends on age, lifestyle, and health.

5. Minimally Invasive Procedures

Newer techniques allow valve replacement without open-heart surgery.

TAVR (Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement)

- Used for aortic stenosis.

- A new valve is threaded through a blood vessel in the leg and placed inside the old one.

- Great for older or high-risk patients.

MitraClip

- A small device that clips the mitral valve leaflets together to reduce leakage.

- Done through a catheter, not open surgery.

These procedures have shorter recovery times and fewer risks.

Can You Live a Normal Life with a Bad Heart Valve?

Yes—many people do.

With proper treatment, lifestyle changes, and regular checkups, most people with valve disease can live full, active lives.

Key tips:

- Take medications as prescribed.

- See your doctor regularly.

- Stay active (but check with your doctor first).

- Eat a heart-healthy diet.

- Avoid smoking and limit alcohol.

- Get antibiotics before certain procedures if advised.

Even people with artificial valves can exercise, travel, and enjoy life.

How to Keep Your Heart Valves Healthy

You can’t change genetics, but you can protect your valves with healthy habits.

1. Prevent Infections

- Treat strep throat quickly to avoid rheumatic fever.

- Practice good dental hygiene—gum disease can lead to heart infections.

- Get recommended vaccines (like flu and pneumonia shots).

2. Control Blood Pressure

High blood pressure strains the heart and valves. Aim for less than 120/80 mm Hg.

3. Manage Cholesterol

High cholesterol leads to artery disease, which affects heart function. Eat less saturated fat and trans fat.

4. Don’t Smoke

Smoking damages blood vessels and increases the risk of heart disease.

5. Exercise Regularly

Aim for 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week—like brisk walking, swimming, or cycling.

6. Eat a Heart-Healthy Diet

Focus on:

- Fruits and vegetables

- Whole grains

- Lean proteins

- Healthy fats (like olive oil, nuts, fish)

- Less salt and sugar

7. Maintain a Healthy Weight

Extra weight makes your heart work harder and increases blood pressure.

8. Limit Alcohol

Drinking too much can weaken the heart muscle and cause irregular rhythms.

Can Babies Be Born with Heart Valve Problems?

Yes. Some babies are born with heart valve defects. This is called congenital heart valve disease.

Common issues include:

- Bicuspid aortic valve – the aortic valve has two leaflets instead of three.

- Pulmonary valve stenosis – the pulmonary valve is too narrow.

- Ebstein’s anomaly – the tricuspid valve is in the wrong place and doesn’t work well.

Many of these conditions can be treated with surgery or catheter procedures. With modern medicine, most children go on to live healthy lives.

Do Heart Valves Wear Out Over Time?

Yes. Like any moving part, heart valves can wear out with age.

- The aortic valve is most likely to calcify (build up calcium) in older adults.

- Biological replacement valves usually last 10–15 years.

- Mechanical valves last longer but can develop clots or tissue overgrowth.

Regular checkups help catch problems early.

Can Exercise Damage Heart Valves?

No—normal exercise is good for your heart and valves.

But extreme, intense exercise over many years (like professional bodybuilding or endurance sports) may increase stress on the heart.

If you have a known valve problem, talk to your doctor before starting a new exercise routine. Most people can exercise safely with guidance.

What Is the “Lub-Dub” Sound of the Heart?

That familiar “lub-dub” is the sound of your heart valves closing.

- “Lub” = mitral and tricuspid valves shutting (after the atria contract).

- “Dub” = aortic and pulmonary valves shutting (after the ventricles contract).

A heart murmur is an extra sound—like a swish or whoosh—caused by turbulent blood flow, often due to a leaky or narrow valve.

Can You Feel a Heart Valve Problem?

Not directly. You can’t feel a valve leaking or narrowing. But you may feel the effects, like:

- Shortness of breath

- Fatigue

- Chest pressure

- Swelling in the legs

These are signs that your heart is struggling.

How Long Does Heart Valve Surgery Take?

- Open-heart valve repair or replacement: 2 to 4 hours.

- Minimally invasive procedures (like TAVR): 1 to 2 hours.

Recovery time varies:

- Open surgery: 6–8 weeks.

- TAVR or MitraClip: 1–2 weeks.

Most people feel much better within a few months.

Can Heart Valves Be Replaced Without Surgery?

Yes—thanks to advances in medicine.

Procedures like TAVR and MitraClip are done through small tubes (catheters) in the leg or chest. No large incisions. No heart-lung machine. These are great options for people who can’t have open surgery.

Final Answer: What Prevents the Backflow of Blood in the Heart?

To sum it all up:

Heart valves are what prevent the backflow of blood in the heart.

There are four valves—tricuspid, pulmonary, mitral, and aortic—each acting like a one-way door. They open to let blood move forward and snap shut to stop it from flowing back.

Without them, your heart couldn’t pump blood efficiently. Every beat depends on these tiny but mighty flaps working perfectly.

While valves can be damaged by age, infection, or disease, most problems can be treated. With early diagnosis, lifestyle changes, and modern medicine, people with valve issues can live long, healthy lives.

The best thing you can do? Take care of your heart. Eat well, stay active, control your blood pressure, and see your doctor regularly.

Because when it comes to your heart valves, prevention is always better than repair.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on What Prevents the Backflow of Blood in the Heart?

Q: What structures in the heart prevent backflow of blood?

The heart valves—tricuspid, pulmonary, mitral, and aortic—prevent backflow. They open to let blood through and close tightly to stop it from moving backward.

Q: What prevents blood from flowing back into the right atrium?

The tricuspid valve closes after blood passes into the right ventricle, preventing backflow into the right atrium.

Q: What stops blood from going back into the lungs from the left ventricle?

The aortic valve closes after each heartbeat, stopping blood from flowing back into the heart (and indirectly, the lungs).

Q: Do all four heart valves prevent backflow?

Yes. All four valves ensure one-way blood flow:

- Tricuspid: prevents backflow to right atrium.

- Pulmonary: prevents backflow to right ventricle.

- Mitral: prevents backflow to left atrium.

- Aortic: prevents backflow to left ventricle.

Q: Can a heart valve repair itself?

No. Heart valves cannot heal or repair themselves. Minor leaks may stay stable, but significant damage requires medical treatment.

Q: What happens if blood flows backward in the heart?

Backward flow (regurgitation) makes the heart work harder. Over time, it can lead to heart enlargement, heart failure, and other complications.

Q: Are heart valve problems serious?

They can be. Mild issues may not cause problems, but severe valve disease can be life-threatening if not treated.

Q: Can you live with a leaky heart valve?

Yes, many people live for years with a mild or moderate leak. Severe leaks may need surgery, but treatment is often very successful.

Q: What is the most common heart valve problem?

Mitral valve prolapse is common, but aortic stenosis is the most serious and fastest-growing valve disease in older adults.

Q: Can stress damage heart valves?

Stress doesn’t directly damage valves, but chronic stress raises blood pressure and heart rate, which can worsen existing heart conditions.

Q: How do doctors check if heart valves are working?

The main test is an echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart). It shows how the valves open and close and whether blood is leaking.

Q: Can you exercise with a heart valve problem?

Yes, most people can—with their doctor’s approval. Exercise strengthens the heart, but intense workouts may need to be avoided in severe cases.

Q: What is the life expectancy after heart valve replacement?

Many people live 10–20 years or more after surgery, especially if they’re otherwise healthy. Biological valves may need replacement, but mechanical valves can last a lifetime.

Q: Can heart valves be replaced more than once?

Yes. If a biological valve wears out, it can be replaced again. Even mechanical valves can be replaced if needed.

Q: Are heart valve problems hereditary?

Some conditions, like bicuspid aortic valve, can run in families. If a close relative had a valve issue, mention it to your doctor.

Q: Can diet affect heart valve health?

Indirectly, yes. A healthy diet helps control blood pressure, cholesterol, and weight—all of which reduce strain on the heart and valves.

Final Thoughts

Your heart valves may be small, but they play a huge role in keeping you alive and healthy. They work silently, tirelessly, with every beat—making sure blood flows forward, never back.

Now you know: heart valves are what prevent the backflow of blood in the heart.

By understanding how they work and what can go wrong, you’re better equipped to protect them. Live heart-healthy. Listen to your body. And never ignore symptoms like shortness of breath or fatigue.

Because when your heart valves are working right, your whole body benefits.